I’ll never forget piling into “Penny,” our copper-colored Ford Mustang, as Mom cranked the engine and pointed us toward a new life in Arkansas. It was the late ‘80s, and I was just a kid, maybe 10, squeezed between my brothers, the hum of the road under us and Whitney Houston’s voice spilling from the radio. That car wasn’t just a ride—it carried my whole world: my family, my fears, and dreams I didn’t even know I had yet. Every mile felt like a leap into the unknown, and looking back, that’s where my story of transitions began.

We were always moving. First, it was D.C. to Landover, Maryland—swapping the buzz of the capital for the Cherry Hills projects, where the playgrounds started clean but soon gave way to shattered storefronts and shady corners. Then came the big one: Mom’s bold announcement, “Hey kids, we’re moving to Arkansas!” I thought she’d lost her mind. I was terrified—leaving behind cousins, friends, everything familiar for a place I couldn’t even picture. But she had that radar intuition, that Wonder Woman gut, and we trusted her. So we packed up Penny, said our goodbyes, and rolled into Pine Bluff, a town poorer than anywhere I’d known. Each move tested me—new schools where I was the outsider, new streets where trouble lurked, new chances to figure out who I was.

Pine Bluff was a shock. We landed in a middle-class pocket, a step up from the cramped apartments of Maryland, but the Jim Crow South hit me like a cold wind. Gangs, drugs, poverty—it wasn’t so different from what we’d left, just dressed in a slower drawl. I’d lie awake some nights, wondering why we couldn’t have stayed in D.C., where Mom’s career had once soared. But then Thom, my stepdad, came into the picture, marrying Mom and lifting us to Little Rock. That two-story, four-bedroom house felt like a mansion, and for a while, life steadied. I was 14 when I started working—summers at Mom’s office at the University of Arkansas Medical School, then flipping burgers at Thom’s McDonald’s. Those jobs were transitions too, from a kid in torn shoes to a teenager learning responsibility, earning my keep.

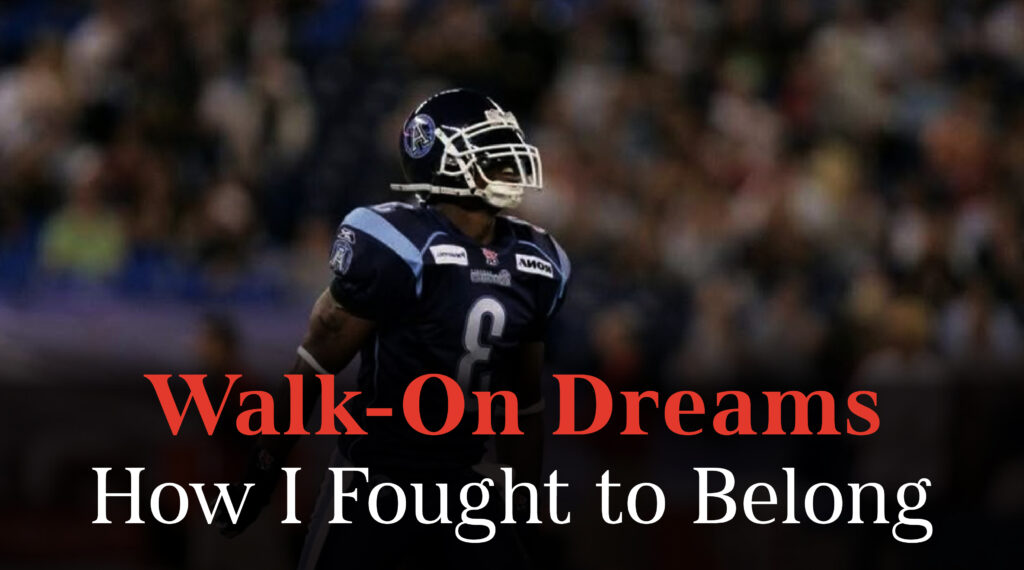

Football was the biggest leap of all. I didn’t step onto the field as some hotshot recruit—I was a walk-on at the University of Arkansas, a nobody with everything to prove. I’ll never forget those first practices in ‘96, my body aching from drills, my mind racing with doubt. I’d traded Penny’s passenger seat for a Razorback jersey, but the road there was paved with late nights, endless reps, and a hunger to escape the embarrassment of my middle school moccasins. I’d run routes until my legs gave out, study playbooks by flashlight, all to turn that walk-on label into something more. It wasn’t easy—teammates had scholarships, pedigrees; I had grit and a prayer. But every hit I took, every yard I gained, was a step into a new version of myself.

Those transitions weren’t smooth. Moving to Arkansas felt like a gamble that didn’t always pay off—friends lost to the streets, Mom’s struggles pulling her back to Maryland while I stayed behind. Football brought its own chaos: the pressure to perform, the sting of being overlooked, the regret of choosing the field over family. But here’s what I learned: life’s a series of shifts, and God’s grace turns the mess into a message. Reinventing myself became my superpower. When Mom’s addiction cost her job, I worked harder. When I felt like an outsider on the team, I ran faster. Every change—geographic, emotional, professional—pushed me to adapt, to find purpose in the upheaval.

Looking back, I see how Penny’s journeys mirrored my own. That car took us from chaos to stability, from poverty to possibility, just like football took me from a kid with no prospects to a man with a mission. I think of Brandon Burlsworth, my teammate, whose own walk-on story ended too soon but showed me what trust in the process looks like. I think of Mom, steering us through uncertainty with a faith I didn’t always understand. Each transition built me—taught me that you don’t break under change, you grow through it. Now, as a coach, I tell my players the same thing: life’s going to shift under you—new towns, new roles, new challenges. Don’t fight it. Lean into it. God’s got a way of taking the detours and making them your highway. From Penny’s rusty frame to the pigskin in my hands, I’ve learned transitions don’t just happen to you—they happen for you. They’ve made me Kahlil—not just a player or a coach, but a man who knows how to keep moving forward, no matter where the road leads.